Seacom strives for greater resilience, the FT uncovers extent of Russia’s subsea sabotage capabilities and preparation, while Japan moves to secure subsea sovereignty

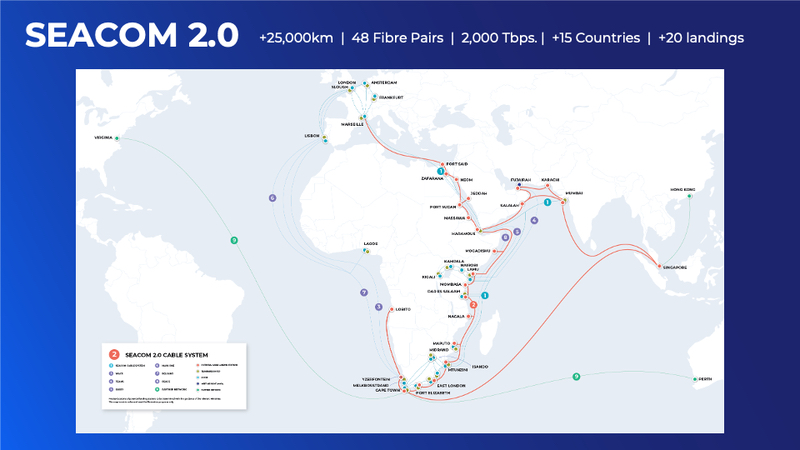

The Pan-African digital infrastructure company Seacom is to build a major new route including subsea infrastructure, called Seacom 2.0. It will connect the Indian Ocean, the Middle East, the Mediterranean, Southern Europe, eastern and southern Africa. Seacom pioneered Africa’s first privately owned subsea cable in 2009.

Seacom 2.0 will be “AI-ready” – what isn’t in marketing? – with the necessary capacity, latencies and loads associated with AI, cloud, and future digital ecosystems.

As the sabotage of subsea cables, as well as accidental damage, has become an acute problem worldwide, Seacom says its new cable “is designed to anticipate disruptions, with diversified routes and neutral landing points to reduce the risk of outages”.

According to The Impact of Submarine Cables on Internet Access Price, and the Role of Competition and Regulation published by the World Bank in June 2025, and produced by the Foundation for Studies and Research on International Development (FERDI), new submarine cables bring down the price of internet access, and especially in Africa where access costs have always been relatively high due in part to scarcer subsea capacity.

Financial Times‘ research is chilling

The Financial Times [FT – subscription required] has been investigating “Moscow’s military spy ship Yantar,” which is laden with kit surveillance equipment, including drones. It’s three-month voyage which started last November “sailed round Norway, down the English Channel and up into the Irish Sea, before looping southwards to the Mediterranean and east towards Suez”.

The ship’s purpose was to map – and possibly damage – undersea cables relied on by Nato allies for internet access, energy, military communications and financial transactions. This is well documented but the FT’s wider research led to it investigating the capabilities and scope of, “Russia’s directorate of deep-sea research, known as Glavnoye Upravlenie Glubokovodnikh Issledovanii or GUGI. Its operations are so classified that only a small group of highly trained Russian hydronauts are privy to them.”

The FT says that most of GUGI’s 50 vessels are submarines and smaller submersibles, some of which can reach depths of 6,000 metres, more than 10 times the depth of a conventional military submarine, as well as surface vessel like Yantar, which can be used as platforms for submersibles and divers.

The FT’s research makes fascinating, if chilling reading, as Russia has become emboldened since its invasion of Ukraine in 2022 and that war has turned into one of attrition rather than the expected rapid victory. The FT quotes Captain David Fields, the UK’s former naval attaché to Moscow, saying, “Russian military thinking places great emphasis on hitting early, hard and where it hurts to prevent escalation to a full-scale war. It has invested a lot of time, money and effort in mapping the critical national infrastructure of their enemies to attack covertly or overtly.

“So if tensions were to dangerously accelerate, Russia could turn the lights out and turn off our energy and communications systems, undermining political will and social cohesion, thereby hoping to prevent escalation to an actual war.”

Japan looks to safeguard subsea infra

Japan’s government is to pay half the cost of a new fleet of undersea cable vessels to be operated by the Japanese conglomerate NEC as its own. NEC is the biggest installer of undersea cable in Asia but currently leases a single cable-laying ship from Norway and rents smaller domestic vessels.

As the Tech Space 2.0 website points out, NEC’s competitors – SubCom of the US, France’s Alacatel Submarine Networks and China’s HMN each operate between two and seven cable ships. Each specialist vessel costs about €300 million. The aim is for the first ship to be operational in 2027, pending approvals.

This is shift in policy for the Japanese government and perhaps a belated recognition of its huge dependence on subsea cables for 99% of its internet access and the need to secure that access.

In 2023 the Japanese government designated subsea cables as vital infrastructure, obliging their operators to report any suspicious activity. In contrast, the French government started the process of nationalising the Alcatel subsea cable business in the same year and completed the nationalisation in 2024. The Chinese operator is heavily subsidised by the state.

Cable ships are immensely expensive to maintain and run, but currently there is a global boom in demand for more cable, driven by AI-mania, cloud computing and 5G. Perhaps even stronger drivers are the need for greater route diversity to provider greater resilience and the desire by a growing number of nations for sovereignty over infrastructure and associated assets as geopolitical tensions escalate and suspected state-sponsored sabotage is on the rise.

Rising tensions, cut cables

While the focus in Europe and the Middle East has tended to be on incidents in the northern seas and the Red Sea which compromised or threatened connectivity, there have been similar incidents in the East. In 2023, Taiwan accused China of severing the two cables that connect the outlying Matsu islands using vessels disguised as fishing boats. The islands were cut off for weeks.

Earlier this year, Taiwan charged a Chinese commercial freighter for allegedly breaking a main cable that links Taiwan to the US, and within weeks another Chinese ship was believed to have cut a second cable. These alleged acts of hostility resulted in the Taiwan’s Coast Guard starting to escort the main cable repair ships and patrolling the major undersea cable routes.